Windows, Microsoft, and the tech industry more broadly are nearing a tipping point. The old model—monolithic firms, centralised IT, and end-to-end control—is fracturing. Revenues are softening, margins are under pressure, and vendors can no longer reinvest their capital as fast as they generate it.

It’s not the first time an industry, even the tech industry, passed a similar tipping point. IBM successfully navigated the transition from departmental to enterprise computing (but seems to be having less success navigating the current tipping point). US Steel, once one of the largest and most profitable firms in the world, transitioned from high-growth high-margin to low-growth low-margin in the late 70s due to a combination of economic headwinds and the maturation of the U.S. domestic market. Kodak and Blockbuster, on the other hand, were unable to chart a course from their old industries to a new digital one.

Time will tell if the industry, or at least some of the firms within it, will unravel, rebalance, or reinvent.

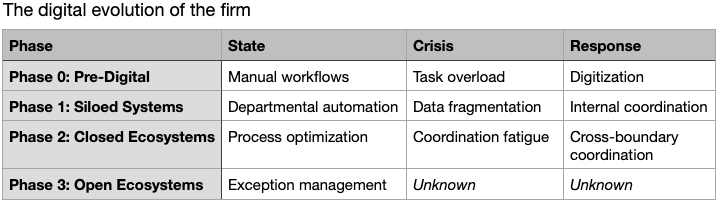

It’s useful to view the history of the tech industry—and technology in business in general—not through the lens of the technology, but in terms of cascading complexity.1 As our technology has improved we’ve tackled bigger problems, but tackling bigger problems has forced us to approach tech differently which has, in turn, required the industry to reconfigure in order to continue growing.

Each shift in phase—from pre-digital to functional digitisation, to closed ecosystems, and now to open ecosystems—has created new winners and losers. Sperry and Burroughs, both classic mainframe-era companies, struggled to adapt to a post-mainframe world and merged to form Unisys, which unsuccessfully pivoted to IT services but is now a shadow of its former scale and ambition. Olivetti thrived in those first two phases, across the first transition, but failed to adapt to the closed ecosystem era. IBM, as mentioned, successfully navigated the first two transitions, but seems to be stumbling on the current one.

The current transition is creating new winners and losers as we speak, and we see examples emerging every week.

Rupert Goodwins argued in The Register, that Windows is a “bad habit” for Microsoft,2 but doesn’t make the connection that it’s a habit propped up by an industry-wide refusal to evolve. The real addiction isn’t just to Windows; it’s to the broken business models of a bygone era. Windows isn’t the cigarette; it’s the nicotine delivery system for a dying industry logic.

All the signs of a firm and industry fighting transition are there. Microsoft’s forced monetisation (Windows 11’s AI push, ads, subscription rumours) are symptomatic of a stagnant market with no new growth avenues, resorting to artificial “innovation” (e.g., unneeded OS updates, LLM hype) to mask declining organic value and a lack of good investment opportunities.3 The article lambasts Windows for becoming an OS that is “both tool and adversary,” prioritising revenue (ads, AI bloat) over usability—a sign of a mature product with nowhere left to grow.

Microsoft has hit an optimisation plateau, and turned to exploiting existing users rather than creating new value. The article also critiques tech firms’ reliance on hyped trends (AI in Windows) to paper over stagnation, calling Windows’ AI features “Uncanny Valley”—what Lichtenstein would call a ‘false attractor’,4 an attempt to bolt ‘new’ onto a collapsing model rather than engaging with the work needed to evolve the model.

This brings us to the obvious question of what future lies on the other side of this tipping point. Predictions are for mugs as they’re usually wrong, but we can lay out what the options are. A logical approach is to use the four standard future scenarios:5 Continued Growth, Collapse, Discipline, and Transformation.

The most desirable approach is Transformation—embrace a deeper reorganisation that fits the new environment (e.g., a platform rebuilt around post-cloud computing models). This means reinventing the firm, or even the whole tech industry, to move it onto a new growth trajectory.

A less satisfactory option is to rebalance—Discipline—to find a new equilibrium (accept contraction and governance adaptation). This would be a managed decline, a transition from high-margin high-growth business champion to a future of more modest ambitions. Think Unisys or US Steel.

The most undesirable is to unravel, which covers Continued Growth and Collapse. Both represent failure, just on different time scales. Continued Growth is the extension of existing trends—inertia wins, complexity piles up, and the system sinks into a long, grinding decline. Collapse, on the other hand, is a failure so profound that a new set of players or architectures rises to displace the old.

Fighting the transition—as Microsoft and the tech industry in general seems to be doing—is implicitly putting oneself on the Continued Growth path, for better or worse.

Our cascading complexity model doesn’t just concern the tech industry and tech firms. There’s also some interesting implications for other stakeholders: the business consumers of the tech industry, and the service providers that tie the two together. The model concerns more than the tech industry: it also shows how adopting technology has changed business. Firms have unbundled, growing revenue while shrinking operational footprint, transforming themselves into open ecosystems in the process.

We can view IT departments—with their CIOs, CTOs, CDOs, and (most recently) CAIOs (Chief AI Officers)—as tech industry outposts in non-technology firms.6 Firms established IT departments because technology shifted from being peripheral to becoming central to business operations. There was a scarcity of expertise and resources, and lack (initially) of external vendors. IT quickly became critical business infrastructure and a major (or the major) CAPEX investment for a firm—it wasn’t uncommon even quite recently for the CIO to have the largest CAPEX budget in many businesses.

All this has changed though, and as the tech industry passes the current turning point, so do the tech outposts in “non-technology” firms. Early on firms had to internalise IT. This is much less true now, and will be even less true in the future. The model for how a firm consumes IT that has been with us for 80 years is not aligned with the new reality. We saw how cloud decimated IT departments in many firms, as they passed responsibility for hardware to cloud providers. IT is rapidly becoming an OPEX cost, and firms don’t need expertise in building, integrating, or running applications.

Nor is there demand for the end-to-end process expertise that has characterised the past 30 years, as the shift to cloud and ecosystems means that an end-to-end process is now a thread through multiple cloud applications owned by different organisations (and provided by different vendors)—processes are being deconstructed into interactions between cloud assets triggered by rules or (increasingly) non-deterministic LLMs.

Similarly, data itself cannot be neatly centralised. In a cloud-native, platform-driven economy, data is fragmented across vendors, clouds, and ecosystems. Data has become the connective tissue—the point of coordination—in an environment where fixed processes can no longer be guaranteed. Firms no longer own the whole journey; they orchestrate it through shared data flows and common meaning structures. The key skill here isn’t enforcing a “single source of truth” inside your walls—it’s navigating between multiple shifting truths outside them. Data sources are distributed, but so are data pools. This has interesting implications for the current tilt to being data centric as in practice “being data-centric” will mean learning to weave coherence across vendor-managed silos commissioned by an ecosystem of partners and suppliers—not dreaming that vendors will agree to harmonise on your terms. Data centricity sounds compelling—but it may be another false attractor, offering the illusion of control in a world where control is diffusing.

Just like the tech industry itself, IT departments face the same four futures: Rebalance (shrink and govern platforms), Transform (dissolve into the business), Continued Growth (persist and stagnate), or Collapse (disintegrate into shadow IT and vendor control). (Continued Growth might sound positive, but in this context it means extending the current model beyond its use-by date—driving inertia and systemic fragility.)

The most obvious future is for IT departments pivot to become internal platform managers and integration specialists—to find a new equilibrium via Discipline. They curate, orchestrate, and govern external platforms and services. They shrink in size but deepen in strategic relevance, ensuring secure and compliant interaction across ecosystems. While this is an obvious future, it’s not clear how likely it is as this expertise is easily available on demand.

The replacement for the traditional IT department is possibly external to the firm altogether. It may be external—thin, business-focused digital advisory functions that specialise in orchestrating platforms, surfacing insights from data, and managing risk across porous organisational boundaries. The strategic skill becomes navigating ecosystems and data—not running internal infrastructure or processes.

We’re already seeing a move in this direction as middle-tier consultancies are building ‘digital’ practices that offer platform selection, governance, and value realisation services. They focus on data, ecosystems, and experience—their digital practices are business-first, technology-second: technology is the medium, not the product. This could be the second path forward, where IT departments unravel—Collapse or Continued Growth—only to be replaced with procurement pushed entirely to vendors and lines of business.

While Collapse would be an abrupt transition, in Continued Growth IT departments persist as bottlenecks—slow, risk-averse, overburdened by legacy systems and compliance needs. They lose credibility with the business, becoming scapegoats for inertia. Shadow IT flourishes in parallel, accelerating fragmentation and governance challenges.

The final option is obviously Transform into something new. IT dissolves into the business. Technology capabilities become embedded within lines of business, with lightweight central functions focusing on enablement, standards, and risk management. “IT department” becomes a coordinating guild rather than a command structure—tech as literacy, not specialty. Technology is no longer something a firm “has”—it’s something a firm flows through.

The future, as I often mention, is uncertain. Any strong prediction should be approached with caution. What’s clear, however, is that we’re witnessing parallel struggles across the technology landscape—from Microsoft’s Windows strategy to traditional IT departments—all stemming from the same fundamental challenge: adapting to a post-closed ecosystem world where value creation has fundamentally changed.

Tech vendors and their enterprise customers find themselves at the same crossroads. The signs of stress—forced monetisation, artificial “innovation,” exploitation of existing users rather than creation of new value—are visible throughout the ecosystem. Those who recognise these patterns can position themselves ahead of the curve.

For leaders navigating this transition, three questions become essential:

Are you fighting to preserve outdated structures, or exploring how to thrive in the new landscape?

Are you investing in false attractors that temporarily mask decline, or pursuing genuine reinvention?

Are you measuring success by old metrics, or developing new frameworks that capture value in an open ecosystem world?

If even technology—the icon of endless reinvention—is struggling to adapt, what hope do industries have where the cracks are still hidden? The answer may lie not in fighting complexity but in embracing it differently. The organisations that will thrive won’t be those that unravel the slowest, but those with the courage to transform before transformation becomes inevitable.

Evans-Greenwood, Peter. “The Great Unraveling.” Substack newsletter. The Puzzle and Its Pieces (blog), March 20, 2025. https://thepuzzleanditspieces.substack.com/p/the-great-unraveling.

Goodwins, Rupert. “Windows Isn’t an OS, It’s a Bad Habit Bordering on Addiction.” The Register (blog), April 28, 2025, sec. Opinion. https://www.theregister.com/2025/04/28/windows_opinion/.

Wiggers, Kyle. “Microsoft Reportedly Pulls Back on Its Data Center Plans.” TechCrunch (blog), April 3, 2025. https://techcrunch.com/2025/04/03/microsoft-reportedly-pulls-back-on-its-data-center-plans/.

What Lichtenstein would call a false attractor emerges when a system, facing deep structural tension, latches onto superficial adaptations that promise relief without addressing the underlying need for transformation. False attractors offer the illusion of renewal — bolting “new” features or technologies onto a collapsing model — but ultimately drain energy and delay necessary change. Rather than engaging in the hard, generative work of evolving a new structure, the system clings to familiar patterns dressed in new language or tools, accelerating fragility rather than resolving it. See Lichtenstein, Benyamin B. Generative Emergence: A New Discipline of Organizational, Entrepreneurial and Social Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Dator, Jim. “Alternative Futures at the Manoa School.” Journal of Futures Studies 14, no. 2 (April 21, 2025). https://jfsdigital.org/articles-and-essays/2009-2/vol-14-no-2-november/articles/futuristsalternative-futures-at-the-manoa-school/.

Though it’s a bit of a laugh to consider any firm these days as a ‘non-technology firm’, as they all use (digital) technology extensively.

Microsoft has decided to slow spending (https://slashdot.org/story/25/04/30/2220242/microsoft-puts-brakes-on-ai-spending-as-profit-increases)—despite strong profits—as capital discipline kicks in, AI compute costs balloon, and the logic of scale begins to strain.

It doesn’t mean AI momentum is ending. It means the system is hitting a temporary ceiling. And the real signal isn’t the spending pause itself—it’s what it might be pointing to:

– That scaling LLMs may be entering diminishing returns

– That infrastructure limits (chips, power, cost-to-serve) are forcing reconfiguration

– That the next wave may require new architectures, not just more scale

This is looking less like disruption and more like rebalance: accept contraction, adapt governance, and manage decline. Think Unisys or US Steel.

This is what I mean when I say transformation rarely starts with tech—it starts with tension.